Learn effective, person-centered strategies for managing aggression and challenging behaviors in nursing homes. Discover de-escalation techniques, root-cause analysis, and non-pharmacological interventions for dementia care. A sudden shout, a refused bath, a hand flung out in frustration, challenging behaviors in a nursing home are often the most distressing and complex issues for staff and families alike.

The instinctive response might be to control or redirect, but modern, person-centered care teaches a different first step: to understand. Aggression or agitation is rarely a willful act; it is almost always a form of communication, a distress signal from a person who may have lost the ability to express needs, pain, or fear in any other way.

Effective management, therefore, shifts from reaction to proactive detective work and compassionate response, aiming to solve the underlying problem rather than merely suppress the symptom.

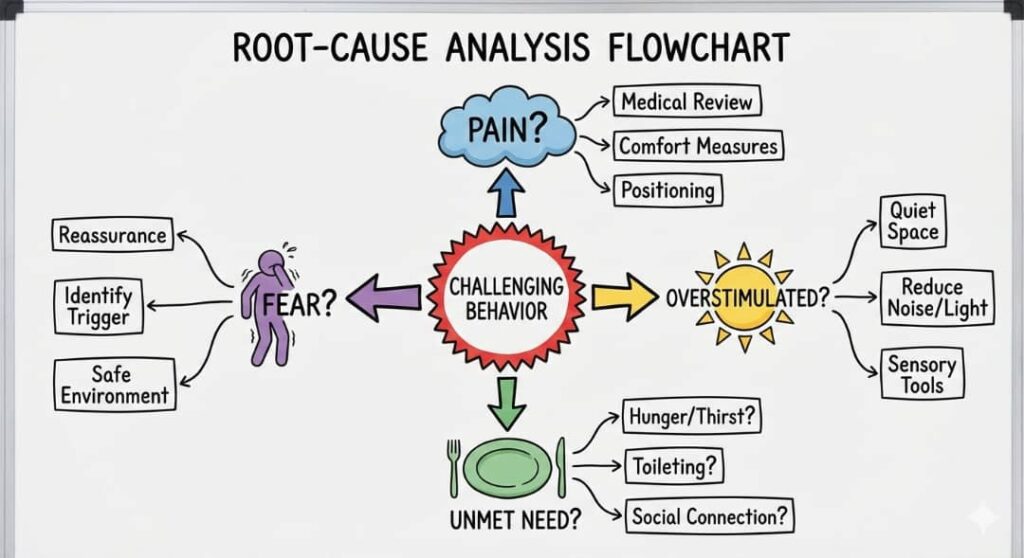

The foundation of managing any challenging behavior is a systematic investigation into its root cause, often called the “ABC” approach: Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence. Staff are trained to document: What happened right before the behavior (the Antecedent)? Was the resident in pain, overstimulated, asked to do something confusing, or interrupted during a preferred activity? What was the specific Behavior, shouting, hitting, refusing? What happened immediately after (the Consequence), did the staff retreat, provide comfort, or escalate?

Tracking these patterns over days often reveals clear, preventable triggers, such as a particular time of day, a certain caregiver’s approach, or an unmet need like hunger, thirst, or pain. Identifying the trigger is the first victory, as it allows for intervention before the behavior even begins.

With potential causes in mind, the frontline strategy becomes de-escalation and therapeutic communication. This requires staff to master their own emotional response. The goal is to project calm, not meet agitation with agitation.

Techniques include using a low, soothing voice, maintaining a non-threatening posture, giving the resident ample personal space, and using simple, clear sentences. Validating the resident’s emotion is powerful, saying, “I see you’re upset, and that’s okay. I’m here to help,” can be disarming. The focus is on connecting and reassuring, not correcting or reasoning. Redirecting to a preferred, calming activity, a favorite song, a walk, a simple folding task can often safely shift the emotional state and provide a “reset.”

For residents with dementia, whose brains may misperceive reality, specialized approaches are essential. Agitation is frequently a direct result of unmet needs or environmental mismatch. A resident trying to “go home” may be expressing a need for security, not a geographic desire. Sundowning (increased agitation in the late afternoon) may be linked to fatigue, low light, or disrupted circadian rhythms.

Non-pharmacological interventions are first-line: ensuring structured routines, maximizing exposure to natural daylight, reducing noise and clutter, and using validation therapy (joining their reality gently) rather than confrontation. Creating “wander-friendly” safe paths and providing sensory-stimulating activities like fidget blankets or music therapy can channel energy constructively. Medication should always be a last resort, used only for clear psychiatric needs and not for staff convenience.

Ultimately, the most sustainable strategy is a proactive, person-centered environment. This means knowing each resident deeply, their life history, preferences, routines, and dislikes and designing care around them. It involves consistent staffing so residents build trusting relationships. It requires training all staff, not just nurses, in these communication and de-escalation skills.

It also means supporting the caregivers themselves; staff who are burnt-out, rushed, or poorly supported are less able to respond with the patience and empathy required. By viewing challenging behaviors as a cry for help rather than a disruption, nursing homes can transform care from crisis management to compassionate support, ensuring dignity and safety for both residents and the people dedicated to their care.

References

American Academy of Family Physicians. (2022, November 14). *Care transition and long-term care options for older adults* (Behavioral management section). Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2022/1100/curbside-long-term-care.html

Groenvynck, L., et al. (2021). Interventions to improve the transition from home to nursing home: A scoping review. *Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 7*. https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214211001498

Federal Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development. (2023). *National policy on ageing* (Dementia care and behavioral management guidelines). Government of Nigeria. Retrieved from https://www.fmhds.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/NATIONAL-POLICY-ON-AGEING-FMHADMSD-VERSION-1.pdf

Elderly Health Service, Department of Health. (n.d.). *Helping elders adjust to long term care* (Aggression de-escalation strategies). Hong Kong Government. Retrieved from https://www.elderly.gov.hk/english/service_providers/helping_elders.html

Health and Care Professions Authority. (2018). *The transition of older people from their own residence to a care home* (Challenging behavior protocols). Retrieved from https://www.hcpa.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/The-Transition-of-Older-People-from-their-own-Residence-to-a-Care-Home.pdf